When someone mentions a “train game,” I usually find it hard to get excited. The moment “18XX” hits the table, my mind tends to wander. I have enjoyed a few titles in the genre, such as Chicago Express, Age of Rail: South Africa, and Iberian Gauge. I am currently playing Ticket to Ride: Legends of the West, which is not strictly an 18XX game but still a train game. Despite these experiences, my bias remains: they all feel very similar. Learn one, and you have essentially learned them all.

While that might be true, it takes more than just a new map to get me interested in playing. I am not particularly skilled at market speculation or company valuation, which puts me at a disadvantage right from the start. However, if you dress the system up with a fresh theme, I can be coaxed to the table. Think of dinosaurs in Cretaceous Rails or bag-building in Lightning Train. A new spin goes a long way for someone like me who isn’t naturally drawn to train games.

Space Rails

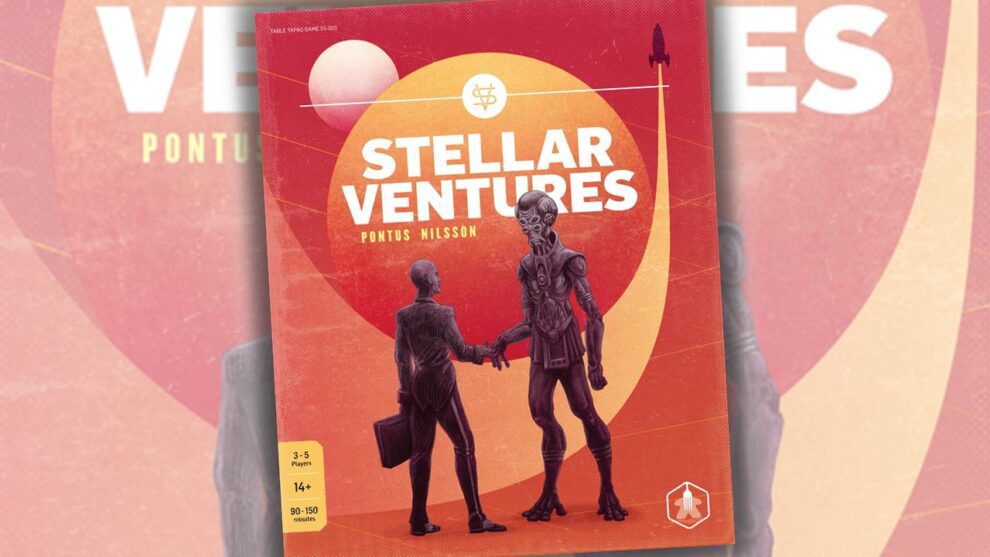

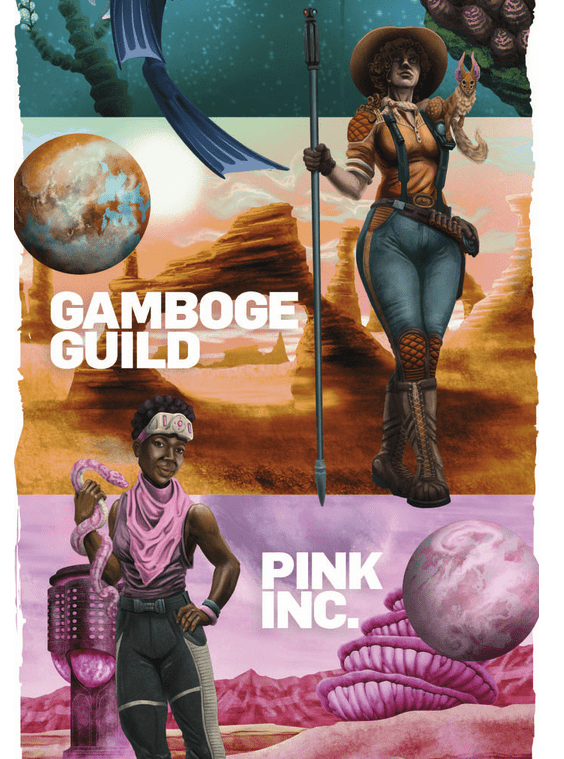

Enter Stellar Ventures, a spacefaring economic game designed by newcomer Pontus Nilsson. At first glance, you might think you have sat down to play Gaia Project, but look closer. This is an investment-and-network puzzle that tests your galactic bookkeeping skills.

Crack open the Corporate Handbook and you are greeted with midcentury-style product ads hyping expansion, investment, and tech development. Then comes the twist: aliens. And they are eager to partner with you, though they come with terms and conditions.

The cover alone hooked me like a pulpy 70s or 80s sci-fi novel. But cube-rails economics combined with alien deals? That might actually be enough to convert me to the genre.

Starting Bid

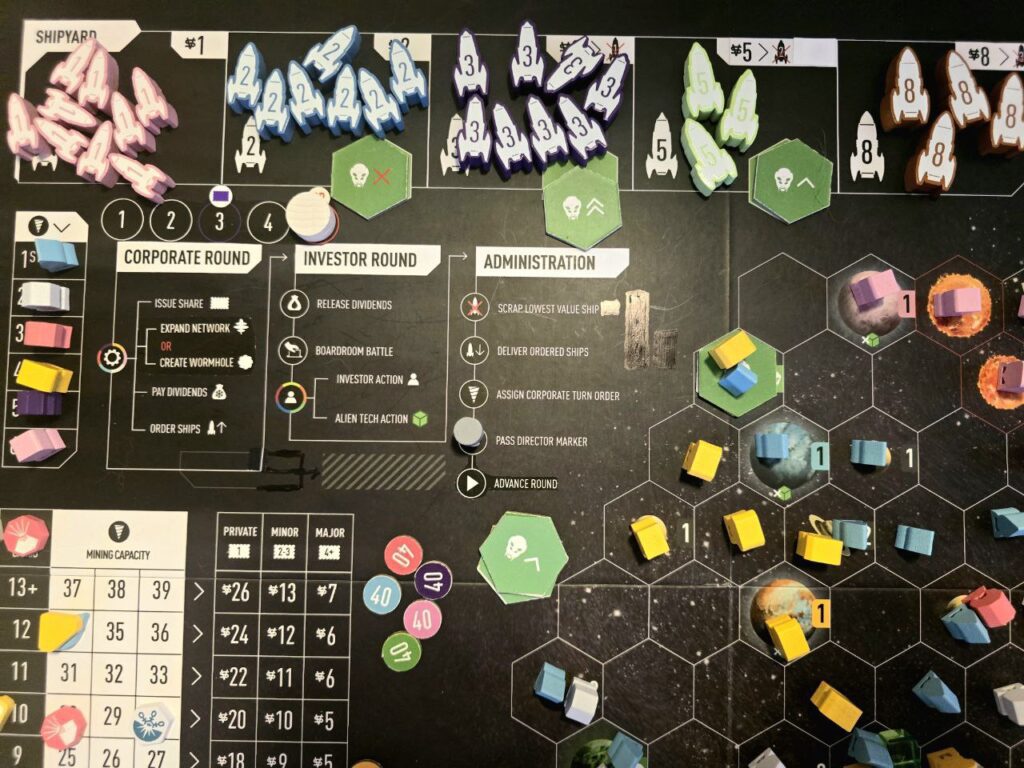

Stellar Ventures plays over five rounds for three to five players, with the most money winning the game. Players act as investors propping up five corporations, with a sixth corporation arriving mid-game.

Initial shares are auctioned in reverse corporate order. It seems procedural at first, until you realize that early shareholders get first dibs on powerful technology. That is when the drama kicks in.

Each corporation starts on a different planet with an asymmetric setup. They have different outpost counts, different nearby terrain, and different early opportunities. Those starting conditions shape each corporation’s risk and reward as an investment.

Rounds follow a clean loop: corporate actions, investor actions, and then administration. In the final round, the game skips straight from corporate actions to endgame scoring.

Corporate Shill

The majority shareholder becomes the President and runs the corporation. You may issue a share to raise cash, then expand by spending corporation money to place up to five outposts. It sounds simple, until one inefficient route comes back to bite you.

Open space is fair game, but anomalies block certain paths. Wormholes, once unlocked, let you skip across space. Neutral planets boost a corporation’s mining value, while building where another corporation already has an outpost costs extra.

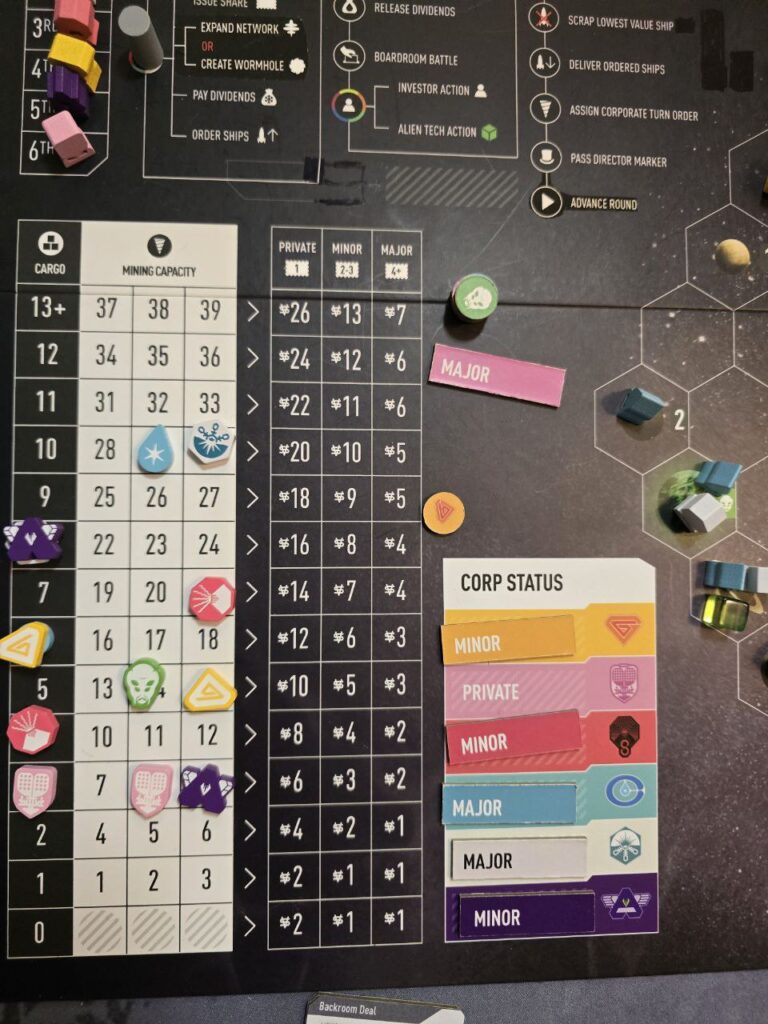

Next comes dividends. They are based on the lower of the corporation’s cargo and mining capacity, adjusted by corporation size. As corporations issue more shares, they grow from private to minor to major, and dividends dilute. This is investing 101.

In a delightful change, dividends are paid by the bank, not from the corporation’s treasury. This flips the usual tension. You can spend aggressively without strangling your own returns. The tradeoff is that corporations feel a little less financially constrained than in harsher stock games, which is great for the pace but slightly softer on consequences.

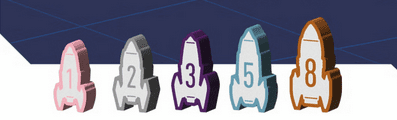

Finally, corporations buy ships, which increases cargo capacity during administration. Ship levels range from 1 to 8. When higher-level ships enter play, lower levels “rust” and get scrapped. Keeping up matters.

Corporations must own a ship. If you cannot afford one, you take an unrepayable loan that drags down the final share value. We had a corporation worth negative dollars per share. Consider yourself warned.

Investor Shenanigans

Now, players put on their investor hats. Dividends become liquid cash, ready for mischief.

First comes voting: players can spend limited vote tokens to force a share sale. It is a perfect moment to dilute dividends, disrupt control, or jump into a hot corporation. Table talk is encouraged. Ties go to the director, which turns negotiations into leverage.

In one game, I forced an auction at the exact right moment, tanked a rival’s majority, and slid into the presidency. It was delicious.

Then each player takes two actions: one investor action and one alien tech action. Investor actions include building outposts, scrapping a corporation’s ship for cash, or permanently removing a vote token to gain an alien tech cube.

Alien tech cubes are like candy. You will always want more, and chasing them can tempt you into inefficient routes.

On the alien tech action, cubes can permanently boost cargo, unlock wormholes, launder into money, or develop planets. Developing a planet doubles its value for all current and future corporations with an outpost there. It creates an immediate, table-wide economic ripple.

Sign Here, Here, and Here

If a corporation has outposts on two or more alien planets, it can sign an agreement. More alien presence means juicier payouts: aliens buy a share, shareholders get a bonus payout, and the corporation gains a new tech tile plus increased endgame share value.

But agreements can be a benefit and a liability rolled into one. If alien mining exceeds the corporation’s mining at the end of the game, a hostile takeover reduces all shares to a value of one. The game telegraphs this pretty well, so it is not a “gotcha” moment. However, at lower player counts, it can feel toothless, which is a shame because it is one of the best thematic pressures in the design.

Market Close

Administration resets the round: ships deliver, increasing cargo capacity. The lowest purchasable ship level is removed, and turn order shifts based on mining capacity.

At the end, corporations liquidate: hostile takeovers are resolved, and share values are calculated from total mining and cargo capacity divided by corporation size.

Congratulations on your workday on the galactic trading floor.

Shareholder Report

I cannot claim enough 18XX mileage to classify Stellar Ventures with authority, but it clearly borrows from cube rails: rusting, dividends, auctions, shared ownership, and presidency pressure. What is missing are the more brutal levers, such as sellable shares, deep stock manipulation, and player-driven endgame triggers.

For me, that is a plus. Stellar Ventures sits in that hybrid euro/cube-rails space alongside games like Irish Gauge and Wabash Cannonball. Put Age of Steam in front of me, and I start micro-stressing over math. Here, the guardrails keep things moving. Dividends and share values are chart-simple and transparent. The round structure is even printed on the board, which makes onboarding painless.

Blocking is minimal, too. Space can host multiple corporations at an added cost, so you are rarely shut out entirely. Instead of racing to lock down track, corporations race toward Mega-Earth: a distant planet with massive mining jumps and only four slots. Fully populated, it can push value up to 15 for each corporation there, which is huge. The puzzle is getting there efficiently with limited outposts, usually from the opposite side of the map, making wormholes feel both necessary and delightfully thematic.

Earnings Call

One of the things I ended up liking more than I expected was that dividends are paid by the bank instead of coming out of a corporation’s treasury. It quietly removes a lot of the pressure I usually feel in heavier economic games. Money is still tight, but it is not suffocating, and I never felt like a single bad decision would ruin a corporation for the rest of the game. It gave me more freedom to build, expand, and take risks, at least until the moment I had to issue another share to raise capital. That is where the tension snaps back into place. I really enjoyed that push and pull between spending aggressively and protecting dividend value.

It also helped shift my mindset toward treating corporations as tools rather than something I had to baby. I found myself pushing them harder than I normally would, knowing that the real consequences would show up later in share value. That made the investor phase feel especially cutthroat in a fun way, as everyone around the table was clearly weighing short-term gains against long-term payoffs. The balancing act of increasing both the mining and cargo capacity for better dividends is a fun puzzle of equilibrium.

Technology tiles ended up being one of my favorite parts of the game. Some of them are immediate boosts, others stick around for the long haul, but almost all of them open up interesting efficiencies or alternate paths. Being able to build through anomalies, snag discounts, permanently boost capacities, or mess with alien tech cubes gave each corporation a distinct feel. There is randomness in what comes out, sure, but it never felt arbitrary. Instead, the technologies gently nudged me toward certain strategies without locking me into them.

Alien agreements added another layer of tension that I really appreciated. The aliens do not just offer benefits; they demand performance. If you rely on them too heavily without maintaining your own mining capacity, they will eventually take over. This creates a constant tension between short-term cash infusions and long-term survival. It is a thematic pressure that fits the space exploration theme perfectly.

The game also shines in its variability. With different corporations, different tech tiles, and the random placement of anomalies and wormholes, no two games feel exactly the same. You have to adapt your strategy based on what is available and what your opponents are doing. It keeps the game fresh and engaging even after multiple plays.

Component quality is solid. The art style evokes that retro-futuristic vibe, with clean icons and readable text. The board is busy but organized, and the cubes and tokens feel good to handle. It is a game that looks good on the table and invites you to start playing.

Learning the game takes a bit of time, especially for players new to stock games or cube rails. However, the rulebook is well-organized, and the reference cards help a lot. Once you get through the first round, the flow becomes intuitive. The game plays in about two hours, which feels right for the depth offered.

Ultimately, Stellar Ventures succeeded where many train games have failed for me. It took a familiar economic system and wrapped it in a theme that I find compelling. The alien interactions, the tech tree, and the spatial puzzle of the map gave me enough new things to think about that I didn’t get bogged down in the financial minutiae. It is a game that respects your time and intelligence, offering a deep strategic experience without unnecessary complexity.

If you enjoy economic games but usually find train games too dry or repetitive, give Stellar Ventures a look. It might just convert you, the same way it did for me. The galaxy is waiting for your investment, but be careful—the aliens are watching your every move.